How did I improve latency by 700% using sync.Pool

23 Dec 2017

We @media.net write superfast backends with at max 30-40ms turn-around time from web-service. We continuously try to reduce money spent per request. This blog enlists a few of our findings.

Precautionary warning: It’s a long post with a lot of code. Comment if I am unclear, abstract or vague at any point.

Why to use sync.Pool?

sync.Pool [1] comes really handy when one wants to reduce the number of allocations happening during the course of a functionality written in Golang. A Pool is a set of temporary objects that may be individually saved and retrieved. fasthttp [2], zerolog [3] are couple of those most popuplar open source Golang libraries which uses sync.Pool at the core of their implementation.

How to use sync.Pool?

Consider the following example:

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

"time"

)

// Pool for our struct A

var pool *sync.Pool

// A dummy struct with a member

type A struct {

Name string

}

// Func to init pool

func initPool() {

pool = &sync.Pool {

New: func()interface{} {

fmt.Println("Returning new A")

return new(A)

},

}

}

// Main func

func main() {

// Initializing pool

initPool()

// Get hold of instance one

one := pool.Get().(*A)

one.Name = "first"

fmt.Printf("one.Name = %s\n", one.Name)

// Submit back the instance after using

pool.Put(one)

// Now the same instance becomes usable by another routine without allocating it again

}

Benchmarks

I picked one of the most commonly used API from our web-service which

- Performs 4 cache queries

- Sends 5 separate events onto Kafka

- Calls 2 separate micro-services synchronously

I ran a load test of 10-rps on my local machine for 10 seconds first on pooled-flow and then on non-pooled flow.

These latencies are higher because this service was running in Pune (India) office and communicating with other microservices running in Oregon (United States) :).

For pooled version

Requests [total, rate] 100, 10.10

Duration [total, attack, wait] 10.189033566s, 9.899999979s, 289.033587ms

Latencies [mean, 50, 95, 99, max] 241.952809ms, 252.716311ms, 476.400585ms, 491.370124ms, 503.938792ms

Bytes In [total, mean] 8400, 84.00

Bytes Out [total, mean] 0, 0.00

Success [ratio] 100.00%

Status Codes [code:count] 200:100

Error Set:

For non-pooled version

Requests [total, rate] 100, 10.10

Duration [total, attack, wait] 13.28824244s, 9.899999931s, 3.388242509s

Latencies [mean, 50, 95, 99, max] 880.57307ms, 325.619739ms, 3.476523432s, 3.685206241s, 3.888228236s

Bytes In [total, mean] 8400, 84.00

Bytes Out [total, mean] 0, 0.00

Success [ratio] 100.00%

Status Codes [code:count] 200:100

Observations

- We get almost 700x performance boost. (95th percentile)

- For most of the objects, the ratio of allocation to reuse was almost 10-15 times. Which means the object was allocated probably 5 times and being used almost 50-70 times, during the course of this benchmark.

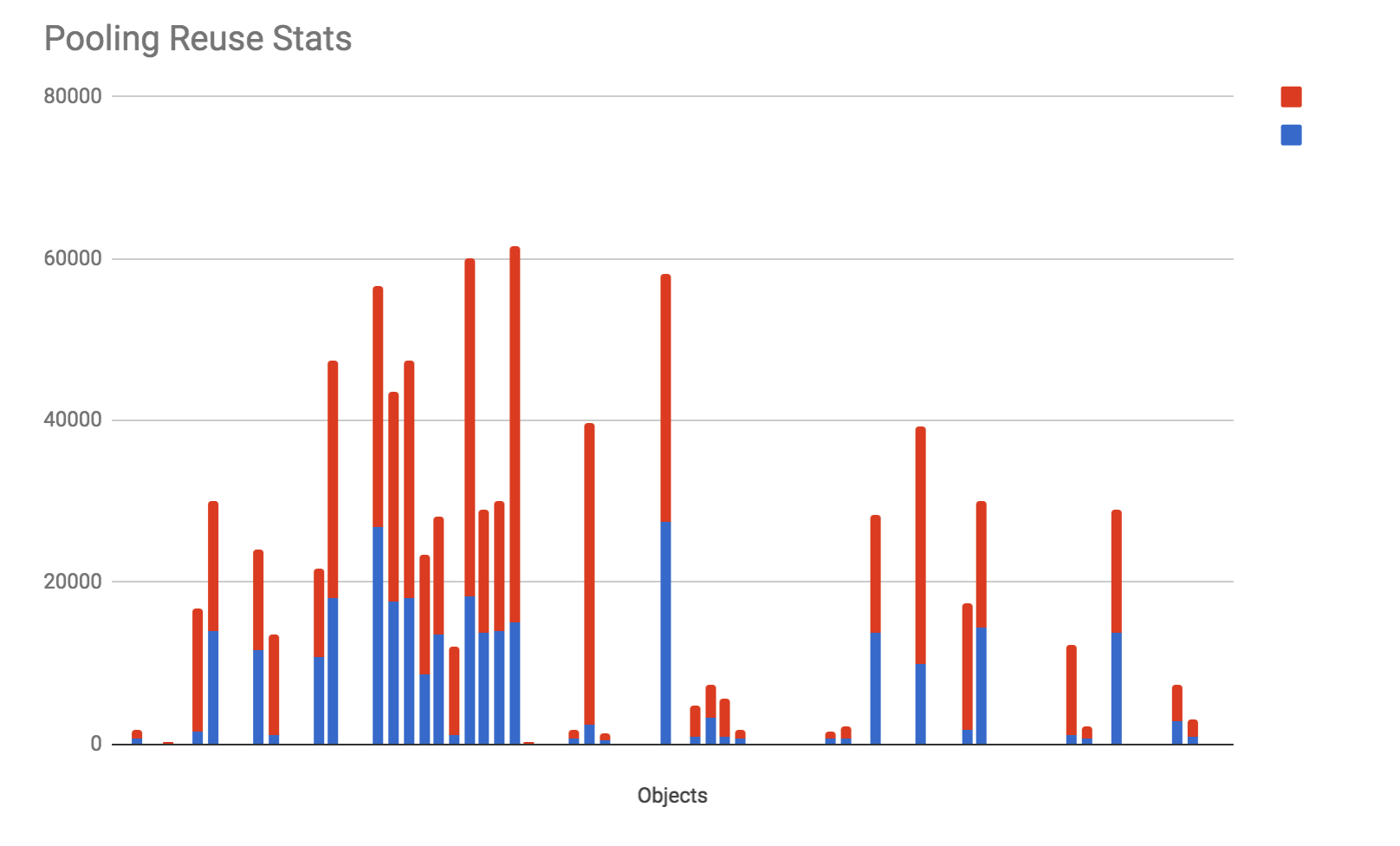

Here are some of the outcomes of one of our services

- Almost 78% of the objects were reused in course of a load test

- During the distributed load, this number will improve a lot

Precautions to be taken while using sync.Pool

What if you pass a pooled object to a go-routine and submit it back to the pool before go-routine yet to complete the execution?

This is a pickle, once you put back the object, it’s ready for reuse. So before you putting back the object inside the pool, you have to be sure that nothing else is using the same object for any other operation.

Example code - play.golang.org

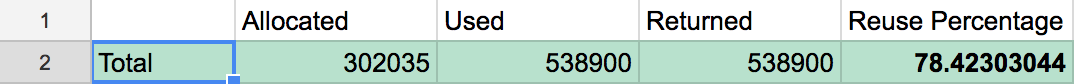

Let’s consider this flow in a more practical use case

Here is the typical flow for a Web-Service API.

Let’s assume that our controller is using pooled struct to read body of the incoming request.

- Go server accepts the request, spawns a go-routine and calls your controller. Typically a func like

func HandleRequest(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request). - Let’s consider it’s a POST API call, and we read the body of the request, map it to a struct A.

- Now through the course of flow, we might do some of the operations on the object in async manner, in a separate go-routine.

- At the end of controller functionality, we put back the object into the pool for reuse.

Refer the following diagram showing the flow:

The issue here is, what if Async Call 1 takes more time and before it completes it’s functionality, your controller has written the response, and object is put back into the pool!

Solution

The only solution to it is manual reference counting for the pooled objects. When I started googling about the solution, I came across a nicely written blog here[4].

Basic flow for Reference Counting will be:

- Increment the counter at the time of Acquiring the object

- Decrement the counter once the routine is done using it

- Increment the counter before passing the object inside a go-routine or channel

- Decrement the counter once the routine is done with processing the object

- An object is only put back into the pool when the reference count is zero.

Implementation

This implementation is highly inspired from the hydrogen18 blog, but has some modifications which are necessary for a practical web app.

We will have an interface to have a blueprint of how a Reference Coutable object will be implemented

// Interface following reference countable interface

// We have provided inbuilt embeddable implementation of the reference countable pool

// This interface just provides the extensibility for the implementation

type ReferenceCountable interface {

// Method to set the current instance

SetInstance(i interface{})

// Method to increment the reference count

IncrementReferenceCount()

// Method to decrement reference count

DecrementReferenceCount()

}

- IncrementReferenceCount to increase the reference count of the current object

- DecrementReferenceCount to decrease the reference count of the current object

We will write a struct that implements this interface, which can be embedded in our own structs.

// Struct representing reference

// This struct is supposed to be embedded inside the object to be pooled

// Along with that incrementing and decrementing the references is highly important specifically around routines

type ReferenceCounter struct {

count *uint32 `sql:"-" json:"-" yaml:"-"`

destination *sync.Pool `sql:"-" json:"-" yaml:"-"`

released *uint32 `sql:"-" json:"-" yaml:"-"`

Instance interface{} `sql:"-" json:"-" yaml:"-"`

reset func(interface{}) error `sql:"-" json:"-" yaml:"-"`

id uint32 `sql:"-" json:"-" yaml:"-"`

}

// Method to increment a reference

func (r ReferenceCounter) IncrementReferenceCount() {

atomic.AddUint32(r.count, 1)

}

// Method to decrement a reference

// If the reference count goes to zero, the object is put back inside the pool

func (r ReferenceCounter) DecrementReferenceCount() {

if atomic.LoadUint32(r.count) == 0 {

panic("this should not happen =>" + reflect.TypeOf(r.Instance).String())

}

if atomic.AddUint32(r.count, ^uint32(0)) == 0 {

atomic.AddUint32(r.released, 1)

if err := r.reset(r.Instance); err != nil {

panic("error while resetting an instance => " + err.Error())

}

r.destination.Put(r.Instance)

r.instance = nil

}

}

// Method to set the current instance

func (r *ReferenceCounter) SetInstance(i interface{}) {

r.instance = i

}

- Reference counter specifically does the job of thread safe reference counting

- Along with that, it puts back the instance associated with the counter into the pool as soon as the reference count becomes zero

- Reset function ideally resets all the members of the instance of an object.

-

This is necessary in most of the practical use cases

- Consider the following struct

type A struct{ First string `json:"f"` Second string `json:"s"` Third int `json:"t"` }- Suppose that while using for the first time we got a JSON like following

{ "f": "one", "t": 1 }- We do the processing and put back the object inside the pool.

- Now we got the second request with following JSON

{ "s": "second" }- Technically the resulting struct should have First as “”, Third as 0. But as we are using pooled objects, First will be “one” and Third will be 1.

- Hence we use a

Resetfunction that reset all the members of the object before puting it back in the pool.

And finally the pool, Reference coutable pool

// Struct representing the pool

type referenceCountedPool struct {

pool *sync.Pool

factory func() ReferenceCountable

returned uint32

allocated uint32

referenced uint32

}

// Method to create a new pool

func NewReferenceCountedPool(factory func(referenceCounter ReferenceCounter) ReferenceCountable, reset func(interface{}) error) *referenceCountedPool {

p := new(referenceCountedPool)

p.pool = new(sync.Pool)

p.pool.New = func() interface{} {

// Incrementing allocated count

atomic.AddUint32(&p.allocated, 1)

c := factory(ReferenceCounter{

count: new(uint32),

destination: p.pool,

released: &p.returned,

reset: reset,

id: p.allocated,

})

return c

}

return p

}

// Method to get new object

func (p *referenceCountedPool) Get() ReferenceCountable {

c := p.pool.Get().(ReferenceCountable)

c.SetInstance(c)

atomic.AddUint32(&p.referenced, 1)

c.IncrementReferenceCount()

return c

}

// Method to return reference counted pool stats

func (p *referenceCountedPool) Stats() map[string]interface{} {

return map[string]interface{}{"allocated": p.allocated, "referenced": p.referenced, "returned": p.returned}

}

ReferenceCountedPoolexpects a factory method that returnsReferenceCoutableinstance i.e. an object implementingReferenceCountable. Here in this example we will be embeddingReferenceCounterwhich will suffice this condition.

Now start using the ReferenceCoutedPool as following:

Consider following struct Event

// Struct representing an event

type Event struct {

pool.ReferenceCounter `sql:"-"`

Name string `json:"name"`

Log string `json:"log"`

Timestamp time.Time `json:"timestamp"`

}

// Method to reset event

func (e *Event) Reset() {

e.Name = ""

e.Log = ""

e.Timestamp = 0

}

// Method to reset Event

// Used by reference countable pool

func ResetEvent(i interface{}) error {

obj, ok := i.(*Event)

if !ok {

errors.New("illegal object sent to ResetEvent", i)

}

obj.Reset()

return nil

}

// Method to create new event

func NewEvent(name, log string, timestamp time.Time) *Event {

e := AcquireEvent()

e.Name = name

e.Log = log

e.Timestamp = timestamp

return e

}

And finally the Event pool

// Event pool

var eventPool = pool.NewReferenceCountedPool(

func(counter pool.ReferenceCounter) pool.ReferenceCountable {

br := new(Event)

br.ReferenceCounter = counter

return br

}, ResetEvent)

// Method to get new Event

func AcquireEvent() *Event {

return eventPool.Get().(*Event)

}

Basic usage:

e := models.NewEvent("test", "this is a test log", time.Now())

defer e.DecrementReferenceCount()

Conclusion

This entire method seems a bit of an overhead, and requires a lot more precision while coding. You miss Reference counting at one place and it could result in a lot of unwanted results. But this works like a charm (see the benchmarks) once you get it right.

Let me know your opinions, doubts, arguments here or at akshaymdeo[at]gmail.com. Happy coding \m/

References

- [1] https://golang.org/pkg/sync/#Pool

- [2] https://github.com/valyala/fasthttp

- [3] https://github.com/rs/zerolog

- [4] http://www.hydrogen18.com/blog/reference-counted-pool-golang.html